[ML01] Introduction: Linear Regression and Gradient Descent

Although this will be a walk through the concept of Linear Regression, mainly from the point of view of Machine Learning, we will also touch upon the mathematical aspects of it and its uses in Statistical data analysis (which is primarily relevant to our lab experiments).

This is the first talk/blog in the Machine Learning series. So, let us start with the very basics.

What is Machine Learning?

In a very crude way, Machine Learning can be thought of as a very detailed study of the art of curve fitting.

We have some data, we have some intuitions about the nature of the data (we have a model), and we try to fit the data into the model.

Let us take an example, and the idea will be more transparent. Suppose the task is to make a decision given some situation. Consider the question: “Whether I am going to play Badminton today or not”. Now, the decision depends on a lot of factors. For example, the day of the week, the time of the day, the number of people coming to play, today’s weather, etc.

So, we have a lot of factors that influence our decisions. Our decision is going to be based on these factors. We can say that our decision would be a function of these factors.

\[\text{decision} = f(factor_0, factor_1, factor_2, ...)\]Given the value of these factors, if we have the function, we can easily make the decision. Now, to actually do it, we have to express (encode) all these factors in terms of some numbers.

For example, we can quickly put the day and time in terms of numbers; weather might be challenging, but we can still think of some aspects which are relevant to us, for example, the temperature, the humidity, how much sunny it is, etc.

Now, we have some factors and answers; both encoded in terms of numbers. Let us say we have $n$ such factors, and we encode them as $x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{n-1}$. Similarly, we encode the answer/decision as $y$ (say).

So according to the motivation above, here we can write that:

\[y = f(x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{n-1})\]Now, the only thing we need to know is the function $f$. If somehow we can get hold of that, given some new situation (set of factors), we can easily calculate the new decision.

Linear Regression

Now let us make an Assumption:

$f$ is a linear function

To put it mathematically, say $f$ is of the form:

\[f(x_0, x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_{n-1}) = b + w_0x_0 + w_1x_1 + w_2x_2 + \ldots + w_{n-1}x_{n-1}\]Note: Linear function does not mean that the function is a straight line. Sure, it is a straight line in 2D, but in 3D, it is a straight line plane; in higher dimensions, it is called a hyperplane.

So here we have the function $f$ in terms of the weights $b, w_0, w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_{n-1}$. Now, we have to find the optimum values of these weights so that the function fits the data best.

Why Learning to do a Linear Fit is enough?

In practice, we often prefer to work with linear functions. This is because they are easy to handle and have been extensively studied. You might wonder, what if the data isn’t linear? Well, in many cases, we can apply simple transformations to the data to make it linear.

Let’s illustrate this concept with an example. Suppose we have a dataset that follows an exponential pattern:

\[y = ae^{bx}\]Now, let’s take the logarithm of both sides:

\[\log y = \log a + bx\]By doing so, if we plot the graph between “$\log y$” and “$x$”, we’ll obtain a straight line. This means we can fit a linear model to the data with just some transformations and, subsequently, extract the values of $a$ and $b$ from the slope and intercept of the line.

Shift to Matrix Notation and Concept of Batch Processing

As we move forward with our linear fitting function, it’s essential to introduce matrix notation and the concept of batch processing. This shift is motivated by the fact that modern computing systems, such as Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), are designed based on Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) principles. This means they can simultaneously perform the same operation on multiple data points, making them more efficient for large-scale computations.

To illustrate this concept, let’s consider a table. In this table, each row represents an example, the columns contain feature values, and the last column contains the ground truth output value. The table looks like this:

| $x_0$ | $x_1$ | $x_2$ | … | $x_{n-1}$ | $y$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 | 3.4 | 5.6 | … | 2.4 | 1.5 |

| 7.8 | 9.0 | 11.2 | … | 4.2 | 0.9 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

| $m^{th}$ | row | filled | with | similar | values |

Now, let’s define the matrices $X$, $W$, $B$, and $Y$:

- $X$ $\in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}$: a matrix containing feature values, where each row represents an example and each column represents a feature.

- $W$ $\in \mathbb{R}^{n \times 1}$: a matrix containing the weights, where each row corresponds to a feature and the single column contains the weight values.

- $B$ $\in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times 1}$: a scalar bias term.

- $Y$ $\in \mathbb{R}^{m \times 1}$: a matrix containing the predicted output values, where each row represents an example and the single column contains the corresponding output value.

Now, Our fitting function for each example $i$ in the dataset was:

\[y_i = f(x_0^{(i)}, x_1^{(i)}, x_2^{(i)}, \ldots, x_{n-1}^{(i)}) = b + w_0x_0^{(i)} + w_1x_1^{(i)} + w_2x_2^{(i)} + \ldots + w_{n-1}x_{n-1}^{(i)}\]With these matrices defined, we can rewrite our linear fitting function in matrix notation as follows:

\[\textbf{Y} = \textbf{X}\textbf{W} + \textbf{B}\]This compact representation not only enables us to perform efficient computations on large datasets using modern computing architectures but also saves us from writing lengthy equations for each example in the dataset.

The Loss Function

Now, we have to define the notion of “best fit”. How do we know that a line fits the data best? We have to define the concept of “error” or “loss”. We have to define a function which will tell us how far the line is from the data. We will call this function the loss function. More loss means the line is far from the data. Less loss implies the line is close to the data.

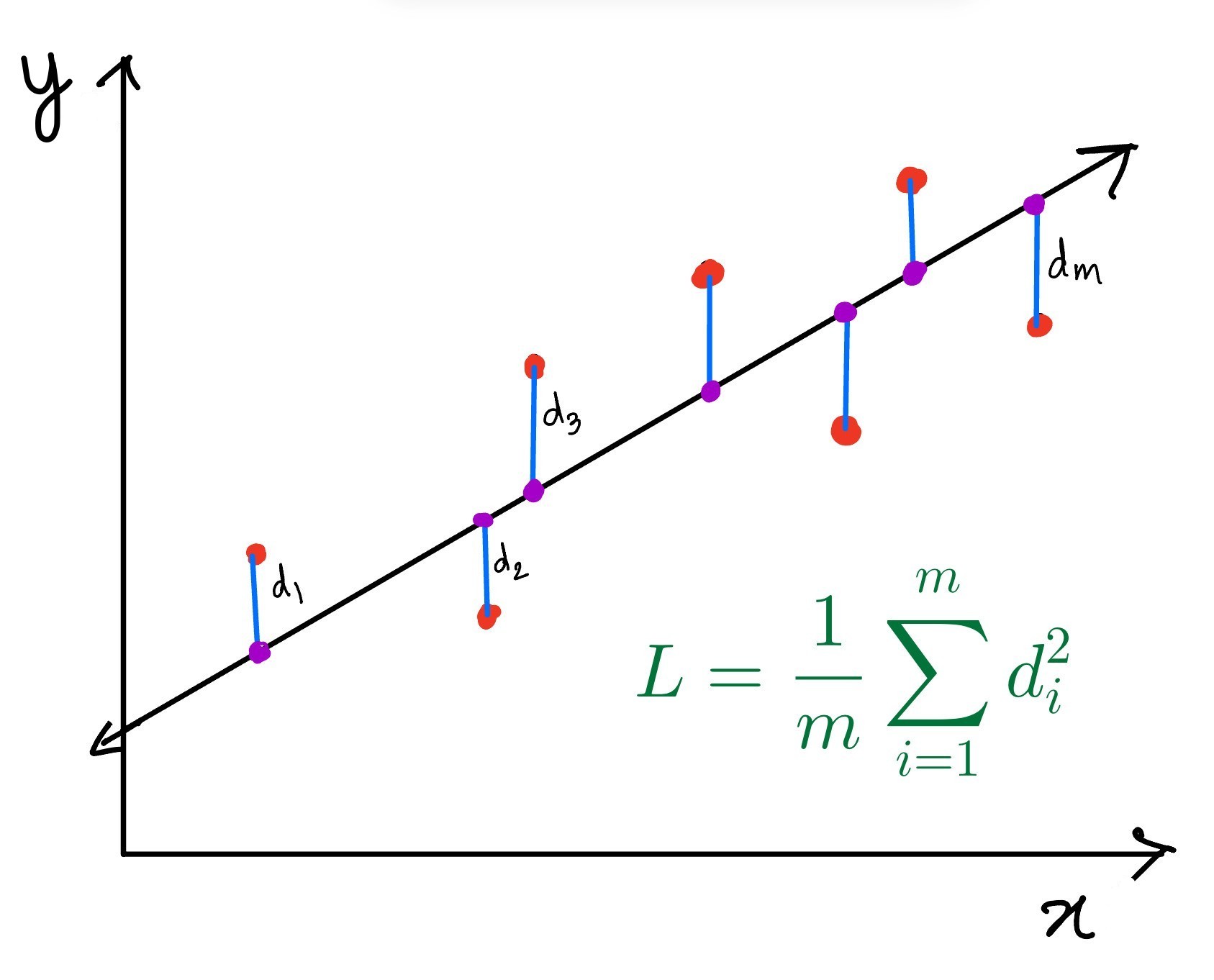

One commonly used loss function for regression tasks is the Mean Squared Error (MSE) Loss, which measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual values.

\[L = \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^{m} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\]where $L$ is the loss, $y_i$ is the true output value for the $i^{th}$ example, and

\[\hat{y}_i = b + w_0x_{i0} + w_1x_{i1} + w_2x_{i2} + \ldots + w_{n-1}x_{i(n-1)}\]is the predicted output value from the model. Now, let’s represent the MSE Loss using matrix notation:

\[L = \frac{1}{m} sum(\textbf{Y} - \hat{\textbf{Y}})^2\]The MSE Loss calculates the average of the squared differences between the ground truth values $\textbf{Y}$ and the predicted values $\hat{\textbf{Y}}$.

In the image below, we can see how the MSE Loss is calculated. In the image, The red dots represent the data points, and the purple dots represent the points on the fitted line that have the same x value $d_i = y_i - \hat{y}_i$.

The MSE Loss is useful for regression tasks because it penalizes large differences between predicted and actual values more heavily than small differences. This encourages the model to produce predictions that are close to the actual values.

Note that the MSE Loss is not suitable for classification tasks, where we need a different type of loss function. Classification tasks fall under logistic regression. For example, we often use the Cross-Entropy Loss in classification tasks, which measures the difference between predicted probabilities and actual labels. We will explore this topic further in another discussion.

Note that the loss function depends on the $\textbf{Y}$ and $\hat{\textbf{Y}}$. And the $\hat{\textbf{Y}}$ depends on the features $X$, the weights $W$ and the bias $B$. Among these, the features $X$ and the true output values $\textbf{Y}$ are given to us and hence are fixed constants. Hence, the loss function is a function of the weights $W$ and the bias $B$.

Gradient Descent

Now, we have the loss function, which is a measure of how good the fit is. And we also know that the minimum value of the loss function is the best fit. So, we have to find the values of the weights $W$ and the bias $B$ for which the value of the loss function is the minimum. We also know that the loss function is quadratic in nature. Hence, it is a parabola (a U-shaped curve) with a single minima.

Why not maxima-minima

Now, to find the minima of a function, we generally use techniques like maxima-minima, where we set the function’s derivative to zero and solve for the variables $W$ and $B$. We could have very well taken the same route here. And it might have worked too. But there is a subtle issue with that approach.

Maxima minima requires us to equate the derivative of the function to zero and solve for the variables. The most efficient ways of solving such systems of linear equations on a computer generally involve inverting matrices. Matrix inversion is computationally intensive, especially for large matrices. The computational complexity of inverting an $n \times n$ matrix is $O(n^3)$, which becomes impractical for huge models and datasets. Additionally, matrix inversion can be numerically unstable if $X^T X$ is not well-conditioned (i.e., it has a large condition number).

Below is a comparison of Gradient Descent and Maxima-Minima, the pros and cons of each approach:

| Criteria | Gradient Descent | Maxima-Minima |

|---|---|---|

| Scalability & Memory Efficiency | More scalable and memory-efficient for large datasets as it iteratively updates parameters without requiring large matrix storage or inversion. | Less scalable and memory-efficient due to the need for storing and inverting large matrices. |

| Solution Accuracy | May not converge to the exact global minimum and can get stuck in local minima. | Provides an exact solution, assuming the matrix is well-conditioned. |

| Computational Intensity & Stability | Computationally less intensive per iteration but requires many iterations; generally stable but depends on learning rate and initialization. | Computationally intensive due to matrix inversion and can be numerically unstable if the matrix is ill-conditioned. |

| Process Nature | Iterative process, which may require many iterations to converge. | One-step process if the system of equations is solved directly. |

Given these considerations, gradient descent is often preferred in machine learning applications for its scalability and efficiency in handling large datasets, even though it may not always reach the exact minimum and can be iterative in nature.

Intuition Behind Gradient Descent

Imagine you are at the top of a mountain, and you want to reach the bottom. You don’t know the exact path, but you can feel the slope under your feet. If you always take a step in the direction where the slope is steepest, you will eventually reach the bottom. This is the intuition behind gradient descent.

In mathematical terms, the gradient is a vector that points toward the steepest increase of the function. By moving in the opposite direction of the gradient, we move towards the minimum value of the function.

Gradient Descent Algorithm

The gradient descent algorithm involves the following steps:

- Initialize the Parameters: Start with some initial values for the weights $W$ and the bias $B$. These can be random values or zeros.

- Compute the Loss: Calculate the Loss after passing the data through the model.

- Compute the Gradient: Calculate the gradient of the loss function with respect to the weights $W$ and the bias $B$.

- Update the Parameters: Update the weights $W$ and the bias $B$ by moving in the direction opposite to the gradient. This can be done using the following update rules: $W := W - \alpha \frac{\partial L}{\partial W},$ $B := B - \alpha \frac{\partial L}{\partial B}$ where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, a small positive number that controls the step size.

- Repeat: Repeat steps 2 to 4 until the loss function converges to a minimum value.

Choosing the Learning Rate

Choosing the right learning rate $\alpha$ is crucial for the convergence of the gradient descent algorithm. If the learning rate is too small, the algorithm will take tiny steps and converge slowly. If the learning rate is too large, the algorithm might overshoot the minimum and fail to converge.

A common practice is to start with a relatively large learning rate and gradually decrease it as the algorithm progresses. This technique is known as learning rate annealing.

Here is a demonstration of the Learning Rate and the number of epochs in action (Note: here we are only training the slope of the line, not the intercept):

m = 5.5949494

Note that, for considerably higher number of epochs (say 10 here) the dependance on the learning rate is less pronounced (negligible change in $m$ for $\alpha$ 0.9 to 2.3). The value of $m$ doesn’t change much with the learning rate. But for a lower number of epochs (say 2 here), the choice of learning rate is crucial.

Types of Gradient Descent

There are several variants of gradient descent, each with their own trade-offs:

- Batch Gradient Descent: Uses the entire training dataset at a time and takes one step. This can be slow for large datasets but provides accurate gradient estimates.

- Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD): Sees each training example to calculate the loss and update the weights (take one step). This can be much faster but introduces more noise in the gradient estimates. This is because one example may not represent the whole dataset well.

- Mini-Batch Gradient Descent: Divides the dataset into batches and updates the gradient after seeing each batch. Passing through all the batches and seeing the whole dataset once is called an epoch. This strikes a balance between the efficiency of SGD and the accuracy of batch gradient descent.

Demonstration Code

Here is a demonstration of the Linear Regression and Gradient Descent algorithm in action. You can adjust the learning rate and the number of epochs to see how the model fits the data.

In today’s discussion, we have covered the basics of linear regression and gradient descent along with the coding aspect of it. We also touched on but chose to leave out specific topics in detail, like the types of gradient descent, how to handle classification tasks etc. We will cover these topics in future discussions.